The higher education sphere has always been a battleground of social mobility. It has symbolised opportunity and achievement, has propped up the distinction between white-collar and blue-collar workplaces, and has been posited as something that is a privilege to experience.

The question of who gets to benefit from such a privilege has been asked for decades, if not centuries, though its subject has frequently changed.

This question has recently become a little more complicated.

We find ourselves in a time of unprecedented change not just in higher education and the workplace, but in how they relate to each other.

On the one hand, more millennials are attending university than any other generation, despite the fee hike in 2012. Access to higher education has frequently been a newsworthy issue: the announcement of a scholarship, funded by grime artist Stormzy, for two black UK students to attend Cambridge University, is only the most recent example. The tide, on all accounts, seems to be turning towards a broadening of access and opportunity to young people of non-white and lower-income backgrounds.

On the other hand, people are starting to talk about the future of the bachelor's degree and its place in our world of work. The phenomenon of 'grade inflation' currently preoccupying higher education officials (wherein first-class degrees are losing value due to their being awarded more frequently) is some tangible support for such talk.

More hypothetically, discussions about AI and automation and their impact on the future workplace raise questions about the actual skillset graduates will need to be armed with. Anecdotally, you won't have to go far to find a recent graduate who finds themselves rarely talking about their degree in a job interview and instead their extra-curricular endeavours.

The university is thus currently the site of huge, often contradictory, change.

How could these changes slow down social mobility?

The structural help offered by institutions will be over before it has begun

Stormzy may have brought access work into the spotlight, but efforts to improve opportunities for disadvantaged students have been going on for years and are only just getting the funding they need.

The Guardian recently published that Oxford University spends roughly £108,000 per low-income student it recruits, including the salary of outreach staff and funding for recruitment activities. That's at least £14m a year, a figure officially required by higher education regulators.

As the skills required to succeed in the world of work move beyond the university as-is, this hard work will inherently misfire.

Recognition will move from official qualifications to attributes largely accessible to privileged students

As degrees become more accessible, more common, and less valued, employers are leaning on skillsets peripheral to the qualification itself. As such, while the glass ceiling might be fading, a glass floor remains.

A 2017 study by the Sutton Trust explores the intricacies of this paradox of opportunity, identifying 'soft' or 'essential life' skills (such as confidence, communication, and motivation) as something that people from higher socio-economic backgrounds have more opportunity to develop.

Abigail McKnight of the London School of Economics is even more damning of this phenomenon in her 2015 government-commissioned report on social mobility issues. She discusses a "little extra something" afforded to privately educated students: "Some of the 'extra' is made up of soft skills - for example - presentation, conduct in social settings, accent - which have little to do with productivity and a lot to do with what economists refer to as 'signalling'."

McKnight isn't subtle in her suggestion that passing for middle-class is a highly valued skill in the labour market. If, as the Sutton Trust predicts, the future holds a net loss of jobs in routine occupations, then protecting the value of hard-earned qualifications will become more and more important in levelling professional opportunity.

Alternatively, employers must be made aware of their unconscious bias towards skillsets that are filtered by economic circumstances out of an individual's control.

Extra-curriculars will become more valued while a door to accessing them is closed

One of the Sutton Trust's recommendations for alleviating the inequality caused by the 'soft' skills bias is that state-funded schools place more of an emphasis on extra-curriculars. It's here, the Trust claims, that soft skills are developed, suggesting a longer school day to make time for activities like 'debating and sports'.

It does not mention, however, a chronic lack of funding that puts comprehensive schools in this position: unable to pay teachers for more hours, hesitant to provide equipment, and thus inevitably incurring extra costs that can't be covered by low-income families.

Higher education institutions therefore provide some of the first accessible pathways to extra-curriculars for many students from low-income backgrounds. Flexible study hours and university-funded activities allow breathing space for involvement in drama, sports, and journalism, as well as the networking opportunities often provided by institutions' large careers budgets.

Even then, time that could be dedicated to these profile-building activities is often necessarily spent working part-time jobs to fund living costs. Those who enter university from higher-income backgrounds and who aren't as time-poor are thus likely to leave with a bulkier CV. Not to mention the career stepping stones provided by having parents in high-paying jobs with professional contacts.

This state of affairs manifests in public perception, too. According to a report by the Social Mobility Commission, 66% of people think that those from low-income backgrounds have less opportunity to get into high-paying jobs like law and accountancy.

Could things improve?

It's harder to judge how an alternative to the bachelor's degree might speed up social mobility, as it's so much farther from today's reality. The absence of a known is one thing; the presence of an unknown is another.

There are, however, clues in the movements of education in general that allow us to consider what this future world of work might look like.

Better recognition and better funding of apprenticeships

An apprenticeship is already a great alternative to university, one that doesn't incur £40k in debt and equips young people with valuable skills outside of academia. In the same Sutton Trust report that identified a perceived inequality in the high-paying job sector, 56% of people thought that access to apprenticeships was equal, regardless of background.

The biggest challenge to the apprenticeship possibly replacing the bachelor's degree will be public perception of it as associated with manual labour, or as a compromise for those without the qualifications to go to university.

In fact, higher apprenticeships (which lead to degree-level qualifications) seek to provide training that is equally if not more valuable than a bachelor's degree, in sectors far beyond the manual.

WhiteHat is one organisation dedicated to busting myths surrounding apprenticeships and to 'democratising access to the best careers'. They are essentially a training provider, but have an envigorated and modern approach to matching young people with the best career opportunities including 1:1 coaching and content-based learning. WhiteHat currently only operates in London and is still a start-up, but with a move away from bachelor's degrees we could see organisations like this growing and in high demand.

No debt, and a chance to start earning straight away

It's true that, despite the rise in tuition fees in 2012 to £9,000 a year, more young people are attending university than ever. Certainly, a renewed financial incentive has lead institutions to push their recruitment strategies to extremes.

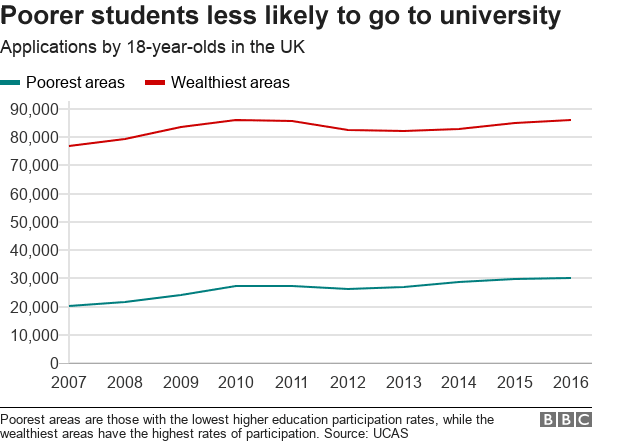

It's also true that people from low-income backgrounds are applying more than ever before. But a BBC article has highlighted that despite this, such students are still far less likely to apply than their peers from higher-income backgrounds.

Source: BBC News

By extension, as long as a bachelor's degree at university is the young professional's first step into the world of work, those who are more privileged will remain one step ahead in this journey.

Apprenticeships, with increased attention, funding and mythbusting work, are a potential alternative – one that doesn't exclude those who can't afford to go to university, but takes them to equal professional heights and pays them from day one.

Courses and schemes that are open to all

Any discussion that speculates on the value of the bachelor's degree is weighing up skills versus knowledge in the future world of work.

As we get closer to a skills-based jobs market, more and more organisations are recognising the need to incorporate these skills into young people's education in an accessible, affordable way. Courses that provide this are popping up external to educational institutions, which with increased demand could mean a whole new set of opportunities for people who haven't gone to university.

Code First: Girls is one example. Co-founded in 2012 by Alice Bentinck and Matt Clifford, the social enterprise provides training in coding for young women. As well as university-based and corporate schemes, CF: G runs free community courses in tens of locations across the country and has provided £4.2 million worth of free education in the UK since 2013. Their aim is to alleviate the lack of women in the tech industry, but a by-product of this is the creation of opportunities for women who haven't taken a university route.

Elsewhere, Ideas Foundation are a charity that work on widening access to high-paying creative industries. They encourage some of the most successful creative organisations in the UK (including Nike, Burberry and The Economist) to 'open their doors to students who don’t normally get a look-in'. They base this work on the statistic that 'last year 92% of creative jobs were held by the most "advantaged" in society'. Projects involve online and in-person sessions that allow young people to generate ideas and develop their creative skills.

Whatever happens, access must be at the heart of any change

We cannot stop the world of work from changing. Companies can expect new priorities and new problems, just as universities, if they care about their students, will need to be constantly rethinking the value of what they provide.

As it stands, institutions like Oxford and Cambridge have teams of professionals working hard every day to encourage underrepresented groups to apply to university. This work is invaluable to a society in which, currently, a bachelor's degree is one of the biggest doors to a successful future.

Whether or not qualifications as we know them are valuable in the future, cohesive efforts from organisations and sectors that champion social mobility can ensure that progress in the working world means progress and equal opportunity for all young professionals.